Currency Debasement Part 4: Conclusion

- Edward Ballsdon

- Jun 19, 2025

- 22 min read

Updated: Jan 13

Introduction

In the three previous articles, I have outlined how “currency debasement” has reduced the spending power of money over time - £1 in your pocket used to buy a lot more than it does today. This is due to the significant increase in the money in circulation, which accelerated in 1971 when the US$ and all Advanced Economies abandoned the Gold Standard. This decision meant that the US Dollar was no longer backed by gold (it cost US$ 38 to buy 1 ounce of Gold in 1971....by the end of 2025 it cost US$ 4,530 to buy that same ounce) and fiat currency could be created with nothing backing it. The expansion of currencies worldwide was undertaken by banks, who lent enormous sums to households and companies and in return received deposits – the result was a swelling of bank balance sheets.

The consequence of currency creation, or currency debasement, is that as time passes, more money is required to buy goods and services, or to buy houses, cars and other large cost items. This is called “inflation”.

Central banks use interest rates to try and keep inflation close to 2%, but their definition of inflation is very tightly defined as the change in money required to buy a determined basket of goods and services (“Consumer Price Inflation” - CPI). they completely ignore the change in money required to buy other items such as houses or stocks and shares (“Asset Price Inflation”- API).

The third article showed that the enormous increase in mortgage loans since 1971 has led to a meteoric rise in house prices. This increase in house prices was significantly larger than the growth in peoples’ salaries, resulting in a marked deterioration in housing "affordability".

When banks lend too much money, this can lead to a banking crisis when an asset price bubble, fuelled by that very debt, is burst. Suddenly the assets of commercial banks, which are the loans they have made and which are no longer being repaid, are worth less than the commercial banks’ deposits (people’s savings entrusted to the bank). To prevent multiple bank bankruptcies, Governments step in and inject new funds to the commercial banks. This is what has happened over the last 30 years in the Japanese, Spanish, Irish, Greek, Portuguese, US (twice), UK and other banking crises.

This required government support occurs just as a government finances are deteriorating due to an economic recession resulting from the banking crisis. Governments need to inject funds to support banks when tax revenues are declining and social security payments are rising, as the recession causes unemployment to rise and profits to decline.

The huge increases in government debt in 2008 and 2009 would have led to large increases to interest rates (in order to attract savers to buy their debt), which would have caused further havoc in many Advanced Economies. However, a new “Monetary Policy Tool” was introduced by Central Bankers in 2009. They created enormous additional amounts of "new currency" to buy existing government debt off domestic savers, who then had cash to buy the new debt being issued by governments in the recession.

This is the Quantitative Easing (QE) operation described in the second article, which brought a material currency debasement in all the countries that employed this tool (USA, UK, Eurozone, Japan, Sweden, Canada, Australia etc.). Central Bankers suggested this was not the sort of “money printing” that caused hyper inflation in the Weimar Republic or Zimbabwe, promising that it would only be "Temporary" in nature. However, the Federal Reserve, Bank of England and the European Central Banks utilized QE for 13 years, and have only unwound a small amount of the new money that they created (between 17% and 30%), whilst the Bank of Japan has hardly reduced its balance sheet at all since it started its QE program in 2011…..

This final article will discuss the impact of QE on economies and on asset prices, showing how it has benefitted asset owners (“Rentiers”) to the detriment of those with no assets or who are in debt (“Renters”). It will show how QE:

has avoided a full repricing of truly expensive assets back down to "fair" or "affordable" values

thereby contributed to a rise in inequalities

allowed investors who invested badly to recoup losses

created a rise in “Zombie” companies that stay solvent despite generating losses

was arguably a political decision undertaken by unelected people

can no longer be reversed

The article will conclude with some thoughts about the future.

“Rentier” vs “Renter”

A “Rentier” is a person who lives on income from property or investments. They own an asset and allow someone else to use it in exchange for a fee. For example, this can be someone who owns a house and lets it out for a monthly rent, or someone who owns a factory and produces goods that people buy, or partners of law firms who sell their legal services to people or businesses. It also includes people who own stocks and shares in companies, or have investments in funds that invest in shares, which represents their ownership of a company, however big or small that might be and receive dividend payments from generated company profits.

A “Renter” is at the other end of the transaction. Someone who rents a flat for a monthly fee, or hires a factory to make a product, or someone who pays accountants or lawyers for their services.

A Renter and Rentier face very different risks to their wealth and financial circumstances.

If the value of a house goes down, then the Rentier’s net worth will decline – this might make no difference to the monthly rental fee she charges to the Renter. The same is true if the value of shares of a company declines – it is very unlikely this will impact the prices of the goods that the company sells. Indeed, the key risk for a Rentier is a change in the value of the asset that they own, as it directly impacts their wealth.

This becomes even more important if the Rentier has borrowed money to buy her asset. As shown in the third article, if the value of the asset declines BELOW the value of the loan, then she will enter a state of “negative equity” – technically she would become bankrupt if she is forced to repay her loan as the value of the asset will not pay off the amount outstanding of her loan. Therefore a Rentier cares about Asset Price Inflation.

A Renter instead is exposed to the change in price of the fee that he is paying for an asset or service. If a person’s salary remains the same, but his monthly rent increases, then he will have less disposable income at the end of the month for food and other costs. Likewise, if his salary increases by 2% in a year, but his food health, fuel and entertainment costs by 8%, he will also feel the pinch as he is left with less money to save each month. The Rentier cares mostly about Consumer Price Inflation.

Asset Price Inflation (API)

As discussed previously, Asset Price Inflation has soared with money creation/currency debasement – API has increased far more than the rise in salaries. As a result, Rentiers have done very well in this period – ask anyone in London or New York who owns a house that they bought 20 or 30 years ago.

Credit Creation and Destruction

In previous “normal” economic cycles, when currency creation was primarily undertaken by banks (and NOT by governments), asset prices that rose to very high valuations would then collapse after the bubble was pricked. A recession would then take hold in which i) banks would no longer lend new money and ii) savers would have to fund government deficits, thereby starving stock and housing markets of their savings.

The chart below shows the extraordinary boom and bust of the Nikkei in Japan in the 80s and 90s and the Nasdaq Dotcom bubble in the US in the 90s and 00s (look at the extremes of the axis!). Note, and this is crucial, how neither stock market recouped its losses – the indices did not bounce back in the near future and return to previous lofty prices.

In those two episodes, there was relatively small government intervention to support failing companies and banks. Japanese Insurers were allowed to go bust in the '90s, as were the plethora of US Dotcom companies in the '00s who racked up huge losses.

Everything changed after the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), as i) governments intervened and injected cash to support failing companies and banks and ii) Central Banks introduced Quantitative Easing (QE) in 2009, whose money creation was used to fund enormous chunks of government debt. This prevented interest rates from rising AND allowed investors to remain invested in stocks and shares, preventing a vicious cycle of people selling stocks into a declining stock market. The result was that stock markets bounced back and regained all their losses (but at a cost that is discussed later) – the chart below shows the US S&P500 and the UK FTSE100 equity indices – what a difference to the Japanese/US Nasdaq chart above.

When the then Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke introduced QE in 2011, my initial reaction was that this would be very inflationary, causing CPI to rise. After all, the Federal Reserve was debasing the US Dollar by creating trillions of new currency to allow the US government to run a huge deficit (in order to support businesses and pay social security benefits to certain parts of the population).

I found out pretty quickly that I was very wrong. This led to a huge lesson in realising the real impact of currency debasement on an economy, financial markets and society. I learnt that you have to follow the money to understand the consequences of money creation!

The money that was generated by the Central Bank and funnelled to governments to fund their deficits, ended up being used to i) prop up Asset Prices (governments supported banks, insurance companies, car manufacturers etc) and ii) reduce taxes. Just as importantly, some governments then embarked on serious “austerity” drives, cutting social security benefits.

The consequence was that stocks and shares, houses and other asset prices bottomed, and rebounded quickly (i.e. API rose). And instead, CPI declined as people’s disposable income slumped. In other words, the money generated supported Rentiers over Renters.

This was an extraordinary lesson and highlighted the importance of recognising 1) how currency can be generated and 2) how that very money creation can impact API and CPI very differently. Chart below shows the appreciation of the S&P 500 US Equity Index (API) and the US CPI.

History is littered with past examples of asset bubbles and the different reactions to them. It’s worth just outlining the two most famous debt-fuelled asset bubbles of the 20th century, which were followed by completely different political and monetary policies:

Great Depression – the 1929 Wall Street Crash

A huge bubble was inflated on the US Stock Exchange in the 1920s (*1). Its roots were in land speculation in Florida, when speculators and companies borrowed huge sums to buy land (in some cases swamps) and houses. Housing Trusts then started borrowing money to buy the shares of real estate companies and Mutual Funds invested in those Trusts. Throughout this period, commercial banks created money on a vast scale that ended up coming back to them as deposits from people who sold houses, Housing Trusts or Equity Funds. The charts below shows the growth of debt (i.e. the money creation- green box) as a percentage of the US’s economic output and the meteoric rise of the US stock exchange.

The Bubble popped in 1929 and everything went into reverse, much like the example shown for the Spanish Real Estate crisis in the previous third article, but on a much bigger scale.

“Negative Equity” caused a multitude of bankruptcies and money contracted as people’s debt had to be written off (red box). As more householders and investors were forced to sell their assets into a market dominated by sellers, all asset prices crashed – the value of money increased! As this crash was taking place, government and banking authorities created no new money or helped the private sector to create new money (at one point the Fed even increased interest rates). As a result, it took many years for house prices and equity markets to revalue. The Dow Jones Industrial Average regained its 1929 peak in 1954, some 25 years later.

Hyper Inflation – The Weimar Republic of the early 1920s

After World War 1, the German government had very large war reparations to pay the Allied Countries, and furthermore they were handicapped as swathes of German industrial companies were confiscated. There came a point where they could no longer afford the reparation payments to the Allies, and so started printing PapierMark (PM - the name of the German currency at the time) to pay their debts (*2).

The effect of this was that the PM lost value as it was debased – more and more PMs were required to buy one ounce of Gold. The government’s fiscal balance deteriorated, and so the government printed more and more money and hyperinflation ensued. The table below shows how quickly matters got out of hand. It did not take long for the wheelbarrow to be worth more than the money it was carrying to buy a loaf of bread. As this currency debasement was taking place, the stock market and house prices soared as people demanded more worthless PMs to exchange any asset (*3).

These are two extreme examples but they show two different effects of currency changes on asset prices.

No Currency Expansion = Asset Prices decline

Currency Expansion = Asset Prices rise

I have no doubt that if Central Banks had not undertaken QE in the 2010s after the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, stock markets, house prices and other asset prices would be much lower today. As a result, Rentiers, who benefitted from 30 year Asset Price Inflation before the GFC, would today be less "wealthy" if QE had never been employed, and Renters would today find assets much more "affordable".

Revaluation and Zombie Companies

An economist by the name of Joseph Schumpeter coined the phrase "Creative Destruction". He put forward a theory that when a company is inefficient and loss making, it should not be supported but be allowed to fail. This is because it will then be replaced by new companies which will be spurred on to develop new technologies that will make them more efficient in order to make a profit.

If you don’t allow this process to happen, then surviving inefficient companies, called zombie companies, will limit the development of new technologies as the zombies will keep their market share and keep the barrier to enter their market high.

Walter Bagehot, a brilliant British economic writer in the 19th century, said something similar, but with respect to interest rates. He said that the market should determine interest rates, as if they were set too low then there would be a "misallocation of capital" that would create inefficient companies that would "crowd out" more profitable companies. He said Central Banks should ONLY intervene and lend money if it was done at punitive high interest rates – in this way this “crowding out” by inefficient companies would be avoided.

If the process of creative destruction was allowed to occur, and support was only granted at high interest costs, then companies would go bankrupt or survive in smaller, leaner and more efficient forms. Company owners and shareholders, as well as people who had lent them money, would bear losses as the companies in which they had invested or lent money lost value. Rentiers in this environment would become poorer.

Roll forward to today.

In the 10 years prior to the pandemic, Central Banks kept interest rates at almost 0% - this was called Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP). Central Bankers were worried about deflation (i.e. the negative of currency creation) and a return of the Great Depression.

In the last 2 years, having raised rates to counter a temporary supply led bout of inflation, due to the severe blockages in the trade routes that caused supply shortages of goods, some Central Banks have now cut rates aggressively, taking rates to low levels again. For example, at the end of 2025 interest rates are at a low 2.0% in Europe, 0% in Switzerland, 2.25% in Canada, 1.75% in Sweden, whilst in Japan they were never meaningfully increased and are a low 0.75%.

In this period there has been an unbelievable growth of Zombie Companies that do not generate a profit and just rely on continuous increases in debt to stay afloat. And China, which has had a ZIRP for 5 years and is awash with zombie companies supported by the state, is flooding the global market with cheap goods, denying Western Companies from generating profits.

It is no wonder that small businesses and large companies are struggling to generate profits, unless they have a monopoly (Nividia, or Google) or very strong brand (supermarkets, Apple) .

Moral Hazard

QE, or money creation to support asset prices, has generated a huge moral hazard (which is often called a “Central Bank Put”). A real life true example explains this well.

In the 2000s, Irish banks extended huge amounts of mortgages to people in Ireland and extended vast amount of loans to real estate companies. This led to a vertiginous increase in money creation and an enormous expansion of the Irish banks’ balance sheet assets. Whilst there was a corresponding rise in deposits at the Banks, it did not keep up with the rise in assets, so banks made up the difference by borrowing money in the financial markets – they issued bonds to investors to attract their savings.

British pension funds invested a significant amount of their funds into these bonds and enjoyed the interest income they received from these investments. As the mortgage loans granted by Irish banks to the Irish population grew, the bonds issued by banks grew and unsurprisingly there was a boom and then then bubble in Irish house prices.

But when the bubble was pricked (due to higher interest rates and a decline in new buyers willing to buy expensive assets), the operation went into reverse. Suddenly house prices collapsed, people and businesses could no longer repay their mortgages and the bank’s assets were worth less than their deposits and bonds.

I hosted the then Irish Finance Minister, Brian Lenihan (RIP) in Milan as he tried to sell his government's rescue plan, called NAMA, to Italian investors. The idea was that NAMA would issue new bonds (IOUs), backed by the government, that would be guaranteed by largely discounted real estate handed over by banks. In exchange the banks would receive cash injections from the government. Sounded like a good plan, similar to the successful "Swedish Good/Bad Bank" model employed in the early 1990s.

Upon close inspection, I noticed that something was missing in the presentation. Such a plan would mean that the people who owned the original bonds issued by the Irish banks would have to take a loss. When I raised this, Mr Lenihan was perplexed – he gazed over to his phalanx of advisors who were also in the dark. Their plan did not envisage these Irish bondholders taking a loss, so the sums and the plan did not add up....

Not long after, Ireland launched a far more ambitious NAMA plan. ALL bank depositors and ALL bank bondholders would be repaid in whole. The effect was to overnight bail out the bond holders on the losses stemming from their poor investments, with this extra cost being borne by the Irish taxpayer. As a direct result, Irish Government Debt jumped from € 80bn to € 215bn (from 24%/GDP to 120%/GDP). And unsurprisingly, a large slug of this debt was financed indirectly by the European Central Bank’s QE program.

When I subsequently raised this issue with a board member of the European Central Bank and a cabinet member of the UK Conservative Government, both confirmed that it was inconceivable that British or other investors in Irish Bank Bonds should ever suffer losses. Even though they had invested poorly and received interest payments, they had then had their losses covered by the state (and thus by the taxpayers), which was backed by the Central Bank QE program.

This is Moral Hazard. And QE has facilitated this in spades. It is called a “Central Bank Put”, whereby an investor who makes a loss on an asset

can sell an asset to a Central Banker at a price that is higher than its true intrinsic value

or will have his loss erased as the central bank introduces QE that drives an appreciation of asset prices.

Without QE this would not be possible - remember the charts above showing the different outcomes of the Nikkei and Nasdaq compared to the S&P in the GFC. Of course the direct beneficiary is the Rentier. Indeed, without QE asset prices would be much lower, benefitting their affordability by the Renter….

Inequalities

Currency debasement and the “Central Bank Put” lead to serious societal inequalities. Over the last 20 years there has been a significant increase in Billionaires, whilst seemingly the poor seem to have got poorer.

The Fed publishes data from a Census which shows the distribution of who in the US owns investments and who owes debt. What is fascinating about their data is the difference between the Median and Mean of each data set:

The Mean is the average amount of investments that people own, or the average amount of debt that is owed.

The Median of some data is the exact half way point of all the people that own investments or owe money.

With respect to investments, there is a significant minority of people in America who own the majority of investments. As a result, there is a large difference between the Mean, or average investment, and the Median investment, which is the amount of money owned by the person who is halfway between the richest person and the person who has very small savings.

Conversely, the much smaller difference between the Mean amount of debt owing and the Median amount of debt owing shows that the amount of debt that people owe is quite similar.

Both of these observations can be seen in the table below, which succinctly summarises the inequality that exists in the US. The chart shows the growth in inequalities and how it is a trend that is visible in many countries. Note how when the Japanese bubble burst in 2000 and DotCom bubble burst in 2001, the income concentration declined and took time to recover as currencies were slowly debased. Compare that to the immediate recovery of inequalities after the GFC in 2009, when the FED utilized QE.

The “Great Financial Crisis” caused only a temporary loss of wealth for Rentiers, as depressed asset prices were immediately supported by QE. The result was that affordability never meaningfully improved for Renters - indeed it has continued to deteriorate as more and more money has been created and currencies further debased.

Who decides QE – Democracy at risk

I hope I have demonstrated the importance of Monetary Policy, set by Central Banks, for a country’s economy. If interest rates are set too low for too long, then huge credit creation (i.e. significant currency debasement) leads to asset bubbles and economic booms are created followed by deep recessions.

Central Banks globally were directly culpable of setting rates that were too low for too long due to i) flawed economic thinking and ii) because they had a mandate to only maintain low and stable CPI, ignoring API. This started with the Bank of Japan in the 80s, but was then followed by the FED, Bank of England and ECB in the 90s and 00s and then by others like the Reserve Bank of Australia, Bank of Canada, Riksbank and RB of New Zealand in the 10s. All these countries saw a huge rise in private sector indebtedness and therefore largescale currency debasement. And because everyone did this, financial markets did not notice, as all currencies lost value.

Central Banks in many Advanced Economies are also responsible for regulating commercial banks. This takes away the argument that reckless Commercial Bank lending is culpable for asset bubbles, as Central banks should have halted them. Indeed, to compound the disaster of recklessly low interest rate setting, many Central Banks allowed Commercial Banks to self-regulate, akin to allowing the fox into the henhouse.

Central Banks, who are supposedly independent of politicians, set interest rates, thereby impacting money creation and currency debasement. They regulate commercial banks and they decide when to undertake QE and by how much. They have thus directly impacted asset valuations and therefore affordability. Crucially, when they chose to utilise QE, they decide who would gain (Rentiers) and who would lose (Renters) when asset prices decline and are subsequently reflated, introducing moral hazard in the process, and so directly impacting societal inequality.

And here lies a tremendously important issue facing populations at large

Central Bankers are not elected by the population of a county whose economic performance they so shape.

Central Bankers are appointed by politicians, and for periods that can last for multiple different governments. They arguably have no accountability to the populations they serve, despite having such a huge influence and direct impact on their lives. Despite failures in causing booms and busts, and failures to predict inflation or disinflation, no Central Banker in any Advanced Economy has been fired or resigned for poor policy or forecasting, or any that have admitted to failing at their jobs (there have been resignations for political or criminal reasons).

I have been fortunate enough to have met scores of Central Bankers from Australia to the United States, including 2 Fed Chairpersons (Bernanke and Yellen), a Governor of the Bank of England and worked with numerous economists who have or have gone on to serve as Central Bankers setting monetary policy.

Its fair to say that Central Bankers have no or little real business experience. They tend to be classically trained economists, and in some cases would have a limited grasp of accounting issues. I have met or worked with two who have a deep rooted grasp of debt and currency debasement – one is Willem Buiter (*4) who served on the MPC and with whom I worked with during the peripheral banking crisis. The other wrote a fabulous book after the GFC crisis (*5), stating that banks need to be restructured to hold far more equity and should be more heavily regulated – his warnings and recommendations have fallen on deaf ears. I recently asked him if many Advanced Economies were in “States of Over Indebtedness” – he replied absolutely, to the surprise of others participators at the meeting.

And politicians?

If you watch political debates, watch their speeches, read their opinion pieces, or discuss finance directly with them, it becomes clear that few have a thorough understanding of finance, let alone currency debasement. This is borne out by two fairly recent ideas that were much discussed in political circles, the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and Mar-a-Lago Accord. Both completely defied accounting principles, but politicians still proposed them as viable solutions, before both were debunked as ridiculous.

It remains a grave issue that today’s politicians are career politicians, many of whom have never worked in business. Given their backgrounds, politicians rely on Central Bankers and Treasury officials to oversee financial markets and economic stability…….

Outlook

In the past, when the stock market rose and fell, interest rates were cut to stimulate new credit. Over time, this currency debasement reflated assets (API) and economies grew again, but with the consequence of ever more indebted households and corporates.

Eventually this can no longer work when people and businesses assume as much debt as they can manage. When this saturation point is reached, low interest rates no longer create new credit in the private sector. Furthermore, because asset prices are so expensive, people can no longer afford to buy them, even with debt, so the private sector (i.e. households and businesses) starts to deleverage as existing borrowers slowly repay debts.

This is what has been happening in Japan since 1990, despite interest rates being set at 0%, or in the US, UK and Europe (and other countries) since the GFC, despite their Central Banks setting very low interest rates. The private sectors ability to leverage further is finished.

This in my view is the main reason why economic growth struggled after the GFC. And this is why governments started spending more, it was to support economies - nearly all major governments are now having to increase their leverage to support economies.

The US, for example, is running an annual budget deficit of 6% of GDP, a level that is double its historic deficit and a magnitude normally only seen during a recession. Running such a huge deficit when an economy is already growing is usually seen as fiscally profligate, but arguably if the deficit was below 3% then the US might just be in a recession......

The table below shows the leveraging and deleveraging of private sectors in different countries over time, and the subsequent rises in government leverage

Source : Bank of International Settlements

So the private sector is deleveraging and the public sector leveraging – how long can this go on for?

What is happening today is nothing new. Professors Reinhart and Rogoff list all the financial crises in 56 countries over eight centuries (*6), a large proportion of which were caused by over indebtedness, currency debasement and asset bubbles. I was very fortunate to discuss the contents and trends laid out in the book with Prof. Rogoff and the key takeaway was understanding what political choices are taken when fiscal debt extremes are met.

The reality is that only 2 political choices exist when debt reaches saturation point:

Don’t debase the currency any more, which will lead to a severe asset price devaluation. This is the outcome described during the US Great Depression example above.

Continue to debase the currency and “kick the can down the road”. This, at extremes, leads to the German Weimar Republic example above.

Prof Rogoff shows that the first scenario is very rarely enacted, as investors are forced to absorb losses on their investments and are unlikely to vote for you in the next elections. In Option 1, when central banks don’t create new money to finance the increasing amounts of government debt, domestic savings have to be transferred from stocks and shares in private companies towards funding the government. This causes stock markets and house prices to decline – leading to angry voters who change governments.

This is why Option 2, currency debasement, is the preferred solution to try and inflate away the problem. By undertaking QE, governments can finance their increased debt stockpiles with the newly created Central Bank money, so asset prices remain artificially high. In the short term the population remains content, but the rising inequalities and a decline in Real prices (cost of living crisis) eventually lead to discontented voters.

Currency debasement to fund increased government borrowing is not a smooth straight line operation. In 2018, the Fed underestimated the government’s funding requirement and the US equity market dropped 17% in 4 months – the Fed quickly pivoted and soothed the market by stating they would support credit creation with lower interest rates.

When Liz Truss caused a panic in the UK Currency and UK Government Bond market, the Bank of England stepped in with more Quantitative Easing. The Fed did the same when Silicon Valley Bank went bankrupt in 2023. And to really hammer home the point, when government finances were put under stress during the Covid crisis, Central Banks employed huge QE programs, thereby increasing and debasing currencies by trillions - these sums contributed to funding the increased government spending to deal with the pandemic.

This is the new normal – the genie cannot be put back in the bottle. Until there is a willingness to revalue asset prices lower, which is politically unappetizing, the private sector will continue deleveraging, necessitating continued large government spending. When there is not enough savings in the system to finance the large government deficits, Central Banks will have to create new money (through QE), further debasing the currency.

Indeed, since I first wrote these articles, the Fed has announced an end to its QT program. The Fed is now expanding its balance sheet again, buying US Government Bills, using poor excuses to justify their actions.

Unfortunately this will widen inequalities further, as the Rentiers will be continually supported to the detriment of Renters. This is driving the rising Populism in so many countries.

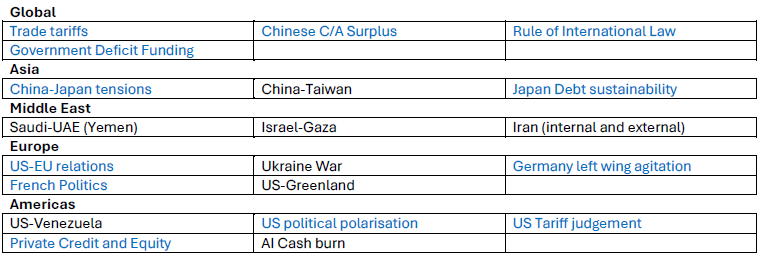

Furthermore, this is also causing the breakdown between neighbouring ally countries with the imposition of selected non-sensical tariffs and geo-political tensions. Below is a list of many geopolitical and macro issues facing multiple countries, two countries or seriously impacting a single country. The world is really in a tough spot.

The issues and events in blue can all be explained by financial imbalances and disturbances. Currency debasement will only make matters worse and those very problems will not be addressed. But as I showed above, historic precedent suggests that over-indebtedness will not be addressed to the detriment of the Rentiers, so you should expect more debasement and more tensions to arise in the future. After all, the problem of leverage is simply enormous (see debt table above).

I shall end here as my scope was to explain currency debasement and how it has

impacted today’s asset prices

shaped society, causing widespread inequalities

occurred with a lack of democracy, as unelected and unaccountable Central Bankers have shaped our future

Hopefully you will now be aware of why there is a rise in inequality and global tensions and what will be required to make assets more affordable, as well as what is a key driver of populism.

I am indebted to the many people who have provided feedback as I put these articles together. Please do get in touch if there is anything that you don’t understand, if you disagree with any of the issues raised or want the content in more detail.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(*1) The Great Crash 1929 – J K Galbraith is a brilliant read

(*2) When Money Dies - Adam Fergusson is a MUST read given current Monetary Policy – I read it in 2010 and recently discovered that the author, a wonderful person, is the father in law of my oldest friends!

(*3) As the German Central Bank was printing ever more money in the 1920s, it also tried other "solutions" to bring confidence in its currency. For example, it issued "Rentenmarks, that were backed by mortgage bonds, which was itself later replaced by Reichsmarks. The current US Treasury's desire to issue "Stablecoins" backed by US Treasury Bonds reminds of the German Central Bank's actions, as a Stablecoin is backed by a fiat instrument, or a "promise to pay" that provides no extra currency value (it does, however offer other benefits, e.g. anti money laundering etc.)

(*4) In 2012, Willem wrote a brilliant piece on Debt when he was Chief Economist at Citi: The Debt of Nations

(*5) The End of Alchemy - Mervyn King

(*6) This Time is Different – Reinhart and Rogoff

شيخ روحاني

شيخ روحاني

رقم شيخ روحاني

شيخ روحاني لجلب الحبيب

الشيخ الروحاني

الشيخ الروحاني

شيخ روحاني سعودي

رقم شيخ روحاني

شيخ روحاني مضمون

Berlinintim

Berlin Intim

جلب الحبيب

سكس العرب

https://www.eljnoub.com/

https://hurenberlin.com/

جلب الحبيب بالشمعة

link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link link